In a

recent podcast titled “Introducing Eastern Orthodoxy” at the Just & Sinner

blog, Lutheran author Jordan Cooper laid some groundwork to help not only

explain why many conservative Lutherans are ‘heading East,’ but also provide an

introduction to Orthodox belief and practice for his largely Lutheran audience.

Since I

have a lot of respect for both Lutherans and their theology—especially that of

Martin Luther as compared to other, later Reformers—I thought it might be

helpful to take some notes and provide a brief response.

Given

that I am responding to my own notes on his talk, it’s possible I have

misunderstood Jordan on points, and so I apologize ahead of time if that’s the

case. I’d also like to say that the purpose of this article is not to engage in

any hostile battle, but to provide balance for what I consider to be a largely

accurate representation of Orthodox Christianity.

Why Are People Converting?

From the

onset, Jordan discusses the conversion phenomenon of the past few decades,

where a number of high-profile evangelicals and even whole church

movements—such as the Evangelical Orthodox Church, led by Peter E. Gillquist

(of blessed memory)—are being received into the Orthodox Church. For him, and

other conservatives in the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod, this begs the

question: ‘Why?’

Unfortunately,

I feel that Jordan makes a mistake that many of us make when faced with this

sort of thing, especially if it involves either friends or loved ones. I have

been guilty myself.

While the

temptation to explain individual or even mass conversions of people from one

religious persuasion to another is strong, it should be resisted. People are

individuals and everyone is on their own path. Attempting to categorize and

ultimately explain away these conversions (and individuals) is neither honest

nor helpful. Jordan wants to categorize these conversions as being mostly done

by under-educated evangelicals or those attracted to the external beauty of

eastern Christianity, but neither is really the primary, motivating factor

(even if they are a supplementary factor for some). I have written before on

the wrong reasons for converting.

Instead,

it is far more helpful to ask these people directly what led to their

conversion, and to dialogue with them (if at all) on the grounds of doctrinal

convictions. Better yet, simply pray for them, love them, and seek to

understand how this step is but one of many on their own salvation journey.

Discerning motives is always best left to God alone.

A Love for Church History and the Early

Church Fathers

Jordan

believes that for the under-educated—those not exposed to either Church history

or the early Church fathers—their conversion is done perhaps in ignorance. Had

they realized that a love for both early Church history and the fathers was

also present in confessional Lutheranism (as with Martin Chemnitz, for example,

in his Examination of the Council of Trent), then a conversion to Orthodoxy or

Roman Catholicism would not be necessary. Jordan also feels that one finds in

Orthodoxy a romanticized version of early Church history, with a mythical

‘consensus of the fathers’ for most beliefs, as well as a naïve understanding

of both Christian history and the struggle for doctrinal orthodoxy.

No doubt,

for many converts to Orthodoxy from other forms of Christianity, a robust

exposure to the early Church and her beliefs is a key motivation behind

conversion. There is a profound, existential experience to be had when one can

read descriptions of the liturgy for catechumens in the third century writings

of a Saint, and then experience that same service—word-for-word and

action-for-action—in the here and now. I was struck by this experience myself,

even as a semi-educated, well-read Protestant of over twenty-six years (at the

time of our conversion).

But

rather than this being a problem of skipping ‘patristic Lutheranism’ (or

Anglicanism, or Presbyterianism) altogether, many take a direct route from

historical study to incarnate reality. In other words, rather than reading

about the Church of the past, in Orthodoxy one finds that same Church in the

present. This is an ontological conversion, not an exercise in academic

curiosity. Rather than attempting to recreate the best elements of our

Christian past in the present, converts to Orthodoxy are deeply convicted—more

often than not—that the Church into which they are being grafted is truly

one-and-the-same with that Church of the third century (or indeed, of any

century). Jordan and others are certainly free to disagree on this point, but

this is where we are.

When it

comes to a romanticized view of history or the Church fathers, I feel this

critique is almost an inescapable one for those not involved with the life and

ministry of the Orthodox Church—in other words, for those on the

outside-looking-in. This is partly due to a lack of resources in the English

language that are both accessible and relevant for those interested in learning

more about the Orthodox Church (but this is slowly changing). Instead,

speculation and oft-repeated half-truths reign supreme (especially on the

Internet).

In

reality, Orthodox Christians and scholars are acutely aware of the struggles

for orthodoxy, beginning as early as Irenaeus’ writings against the Gnostics

and continuing all the way down until the present, where any number of

struggles can be easily numbered (Lord, have mercy). There was no ‘golden age’

of the Church, nor will there ever be one this side of the resurrection. Some

of our greatest heroes of faith died either in exile (St. John Chrysostom, St.

Athanasius of Alexandria) or with their limbs or tongues having been severed

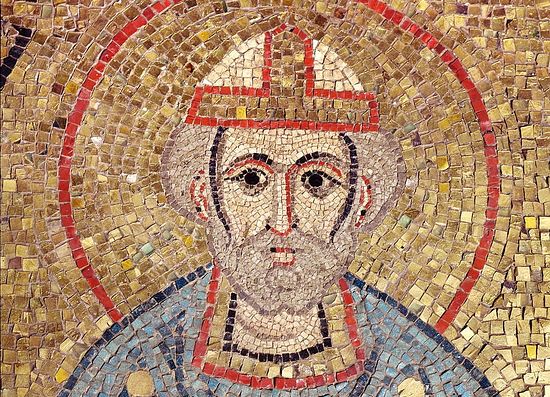

(St. Maximos the Confessor). Even ‘jolly’ Saint Nicholas died with a broken

nose and having slapped Arius in the face. Christian history is indeed a complicated,

messy thing. The theanthropic Body of Christ is never without the ‘anthropos’

and a struggle for both doctrinal and moral purity.

On the

issue of a ‘consensus of the Fathers,’ it is somewhat inaccurate to attribute

this perspective to the Orthodox Church as the sole or even primary litmus test

of orthodoxy. In fact, this perspective has more heritage with the Reformers

than with the Orthodox Church. For Orthodoxy, ‘dogma’ is defined by conciliar

consensus as laid out in the Ecumenical Councils. Orthodox dogma, then, is

actually restricted to a rather limited number of doctrinal ‘boundaries’ (Greek

‘Horos’), within which all dialogue, debate, and pious opinion takes place.

Even doctrines such as deification have not been ‘dogmatized’ in the eastern tradition,

but represent instead a prevailing consensus of theological expression. The

same could be said for any number of Orthodox doctrines that are often wrongly

characterized by the non-Orthodox as ‘the Orthodox position’ on a topic (more

on this later).

As an

aside, the so-called canon of St. Vincent of Lérins (often cited as an example

of requiring patristic consensus) does not describe the manner in which dogma

is determined, but rather how discerning Christians throughout history are to

engage in a proper discussion of matters that are not dogmatic—that is, that

are not a matter of Ecumenical dogma—and only one of these three options (they

are not to be simultaneously applied, but rather successively) involves a

‘consensus’ of the fathers.

From the

Orthodox perspective, Church fathers are alive today just as they were in the

fourth century. There was no charismatic cessation of fathers at the close of

the Seventh Ecumenical Council, and our services often conclude by invoking the

prayers of “our holy fathers” who are among us. Christian writers in the Church

today are themselves a part of our living, breathing, holy tradition. While

some popular-level works might be misleading in characterizing Orthodoxy as a

faith always looking backwards, we are very much a living, present, and dynamic

faith. What we hold to be true is not true because it is old, but rather

because it is orthodox.

Greek East and Latin West

Jordan

rightly notes a growing distinction between the theological development of the

Latin-speaking West and the Greek-speaking East, as early as even the third

century. For example, the third century teacher Tertullian of Carthage (A.D.

160–225)—later in his life a member of the heretical Montanist sect—is often

termed the ‘Father of Latin Theology.’ He mentions key figures among the

Greeks, including both Ss. Maximos the Confessor and Gregory Palamas, whose

theology was no doubt influential on late-medieval and even present-day,

Orthodox theology.

One of

the specific distinctions he notes is the addition of the Filioque (Latin “and

the Son”) to the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381—an addition first made

by Spanish Christians in the sixth century, and later officially sanctioned by

Rome in the early-eleventh century. I appreciated most of what Jordan had to

say on this issue, admitting that the Latin Christians were not exactly

charitable in their unilateral decision to amend the creed. However, like many

Orthodox Christians, I do not necessarily think that an amendment to the creed

is impossible (I would say it is unnecessary). Instead, the issue is the

orthodoxy (or non-orthodoxy) behind this statement and its implications.

While I

likely disagree with him on the underlying theology, I respect Jordan’s

confessional convictions that—as a faithful Lutheran abiding by the Book of

Concord—he cannot rightly advocate a removal of the Filioque from their usage

of the creed.

Jordan also

mentions the notion of doctrinal development in the Roman church today, in

distinction from the East. For example, he mentions the number of additional

‘Ecumenical Councils’ assembled by the Roman church since the Seventh

Ecumenical Council (A.D. 787), all of which are less-than-grand in both scale

and emphasis when compared with the first seven.

But here

I think Jordan commits another common error when it comes to understanding the

Orthodox Church, saying we believe ‘all heresy’ was stopped at the Seventh

Ecumenical Council, with no need for a similar ‘development of doctrine.’ (He also attributes the celebration of the

Triumph of Orthodoxy with the seventh council, a celebration that actually

first commemorated the Synod of Constantinople in 843 under the Empress

Theodora—but this is a common confusion.)

For

example, it should be noted that there are a number of Orthodox Christians and

theologians today who would term the fourth ecumenical synod in Constantinople

(A.D. 879–880) as the Eighth Ecumenical Council. This synod is referred to as

such in both the fifteenth century writings of St. Mark of Ephesus and the

Encyclical of the Eastern Patriarchs (1848), written in response to Pope Pius

IX’s Epistle to the Easterns. In the Greek church today, there are synodal

discussions for affirming this synod as well as the synods dealing with the

Palamite controversy of 1341–1351 as the Eighth and Ninth Ecumenical Councils,

respectively. A pan-Orthodox council could someday rule this to be official

Church teaching.

Beyond

this, there have been a number of formative, ecumenical statements or doctrinal

formulations on the part of the eastern churches since the eighth century.

Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, in fact, outlines these events and statements in

The Orthodox Church, which Jordan references several times in his discussion.

But we have to keep in mind what I stated already: our dogmatic boundaries are

set, with a great deal of freedom allowed within. The necessity for continual

dogmatic development is not granted on the part of Orthodox Christians,

especially given our predilection towards apophaticism.

And

finally, on this point, one cannot neglect the historical circumstances

surrounding the Orthodox Church since the fall of Constantinople (1453). For

centuries, the Church was—at best—operating in a state of persecuted ‘survival

mode,’ praying only that she would survive for another generation. This has

continued all the way until the fall of the Iron Curtain, and persists even

today. Thankfully, in many places where Orthodoxy is represented, this is no

longer the case. But one cannot ignore even the present sufferings of our

brothers and sisters in Egypt, Syria, Turkey, and now Ukraine—where the

prospect of ‘dogmatic development’ is the furthest thing from anyone’s mind.

I would

contend that the presence of dogmatic development is a symptom of stagnancy,

not the solution against it.

The Legacy of Saint Augustine of Hippo

His talk

then shifts to both the theology and influence of St. Augustine on both Western

Christianity as a whole, and Martin Luther in particular.

Mentioning

Augustine’s perspectives on human depravity, original sin, and double

predestination, Jordan states that Augustine has not been nearly as influential

in the East, and that we don’t consider him to be ‘fully’ a Saint, preferring

to refer to him only as ‘Blessed.’

Throughout

his podcast, Jordan mentions a few different source books for his exposure to

Orthodox doctrine. It has to be noted here that some of the works he’s relying

upon—especially that of Lossky, great as it is—represent a particular

perspective of Orthodox theological expression, motivated by various historical

circumstances. Again, not everything written by an Orthodox Christian—clergy or

otherwise—is representative of the dogmatic beliefs of the Church (of which

there are precious few). He is taking the opinions of a few as normative for

the entire Church. There are certainly some Orthodox people over the past

century or so who have over-reacted to a Western ‘captivity’ of their

generation in Orthodox thought, focusing this divergence on the figure and

writings of St. Augustine—but this does not represent any official Church

teaching.

In fact,

the Fifth Ecumenical Council (A.D. 553, held in the East) numbers Augustine among

a select group of fathers to be highly revered for both their piety and

theological writings. This does not mean they are infallible—and some of their

writings are more important than others—but it certainly, and with conciliar,

dogmatic authority, leaves no room whatsoever to deny that Augustine is a

Saint. On this point we must state that those who would deem him otherwise are

simply wrong. (Also, Orthodox Christians do not have ‘levels’ of distinction

for venerated figures, so ‘Blessed’ is not a designation ‘less than’ that of

‘Saint,’ for example–any more than calling the Theotokos ‘Blessed’ makes her

less than a Saint.)

While

Orthodox Christians might disagree with much of Augustine-via-Aquinas or the

later Reformers, we venerate and appreciate Augustine for the areas in which he

was most influential on the continuing life of the Church: e.g. his

anti-Donatist writings, his position on the canon and text of scripture, his

work on baptism and the other Christian mysteries, and so on. Augustine-via-Maximos

the Confessor and other work being done in our own day is far more interesting

to eastern scholars, of course, but we revere him nonetheless. Many Orthodox

Christians take Augustine as their baptismal name and even more venerate his

holy icon—we love St. Augustine.

Monergism, Original Sin, and Semi-Pelagianism

The

figure of Augustine and his influence on the West (and supposed disdain in the

East) leads Jordan to a brief discussion of the differences between monergism

and synergism.

Essentially,

monergism is the belief that all of a person’s salvation—from beginning to

end—is a work entirely of God and his Grace, while synergism teaches that God

begins the work of salvation by Grace, but a person must then cooperate with

God’s Grace for the remainder of their life. Jordan mentions the figure of John

Cassian as a champion of the doctrine of synergism, revered by the East and

rejected by the West (or at least, not venerated as a Saint). He also briefly

mentions the doctrinal position of Semi-Pelagianism, supposedly held by both

John Cassian and even present-day Orthodox Christians. Jordan notes that the

Orthodox are not full-blown Pelagians, but that we don’t see original sin as a

total or complete ‘corruption’ of human nature. For the East, says Jordan, the

emphasis is not on the sin or guilt of Adam, but on the consequence of death.

There is

almost a limitless amount that could be written on these few points, so I will

do my best to be brief.

First, it

must be stated emphatically that St. Augustine did not hold to monergism (a

Reformation doctrine), but is in fact a synergist along with practically every

other father and early Christian authority. As just one example, Augustine

shares a concise analogy of a tree, illustrating the cooperation between both

God and man in salvation (On the Grace of Christ 1.19.20). The grace of God

first makes an evil tree good (at baptism), and then “God co-operates in the

production of fruit in good trees.”

This is

the position taken by the Second Synod of Orange (A.D. 529), a council

curiously appealed to by Calvinists as ‘patristic evidence’ of both monergism

and the Doctrines of Grace:

According to the catholic faith we also

believe that after grace has been received through baptism, all baptized persons

have the ability and responsibility, if they desire to labor faithfully, to

perform with the aid and cooperation of Christ what is of essential importance

in regard to the salvation of their soul.

And

regarding double-predestination (whether taught by Augustine or not), this

council concludes:

We not only do not believe that any are

foreordained to evil by the power of God, but even state with utter abhorrence

that if there are those who want to believe so evil a thing, they are anathema.

Semi-Pelagianism

itself is also an invention of the sixteenth century, and does not exist in any

discussions of the fifth or sixth (the term is coined in 1577). While Saints

such as John Cassian and Vincent of Lérins are often wrongly associated with

this fabricated heterodoxy, they are actually in agreement

with—contra-monergism—the Second Synod of Orange. This council was an orthodox

compromise between the isolated speculations of St. Augustine and that of the

heretical Pelagians. St. Vincent himself mentions this debate in his

Commonitory around the time of Chalcedon (A.D. 451), where he decries the

doctrine of double-predestination. For those like Cassian, salvation is of

Grace from beginning to end, while not ignoring both the reality and necessity

of man’s cooperation with that Grace from baptism to last breath.

It is

sometimes claimed that John Cassian is not venerated as a Saint by Rome, but

this is not really true. In the present Catechism of the Catholic Church, he is

cited twice (as “St. John Cassian,” cf. CCC 1866, 2785). Denzinger refers to

him a number of times in the Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma as “St. John

Cassian.” His feast day—while admittedly out of prominence in the latest

Vatican reforms of the Martyrologium Romanum—is July 23 (Feb. 29 for the Orthodox

and Anglicans). Cassian was also incredibly influential on the foundations of

Western, Benedictine monasticism, along with the likes of Pachomius and the

Egyptian or ‘desert fathers’ of the east. He is not widely beloved as he once

was in the Christian West, but he is certainly not rejected or seen as less

than a Saint and father of the Church.

On the

topic of original vs. ancestral sin, this is another example of taking certain,

even popular, Orthodox writings on a doctrinal perspective, and assuming them

as normative, exclusive, and dogmatic.

It is

certainly the case that the majority of Greek and even Slavic theology on

original sin over the past century has focused on the inheritance of death and

corruption from Adam. This is also what often gets emphasized in introductory

or popular-level discourse. In part, this has to do with the fact that this is

a narrative elevated in the vast majority of our liturgical services (hymns and

prayers) related to the subject. For example, the great Paschal (Easter) hymn

refrains:

Christ is risen from the dead,

Trampling down death by death,

And upon those in the tombs bestowing life.

While the

overwhelming emphasis of eastern works on the topic of original sin focuses on

the consequence of both death and corruption (and their reversal in Christ’s

death and resurrection), this does not mean we reject a susceptibility and even

strong inclination towards sin as a result of the Fall. As Jordan would likely

agree, these viewpoints are not mutually exclusive—it is simply a matter of

emphasis. And that emphasis has changed over time, with confessions or

catechisms of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries dealing more with the

psychical or moral effects of original sin than simply death and corruption

alone.

For more

on the other angle of Orthodox belief on original sin, I would recommend two

essays: Original Sin and Orthodoxy: Reflections on Carthage and Original Sin

and Ephesus: Carthage’s Influence on the East. As one can discern, the focus is

on conciliar, Ecumenical decrees, not a perceived ‘consensus of the fathers’ or

the viewpoints of a few, even key, writers.

East vs. West?

Jordan

feels that many Orthodox Christians are engaged in an over-reaction to what we

term ‘Western’ theology. He sees this in Lossky, and finds that for such, bad

theology is associated with being ‘Western,’ while orthodox theology is always

‘Eastern.’

On the

one hand, I think a lot of this is our own fault. As mentioned earlier, there

is definitely a part of Orthodoxy over the past century or so that has drawn

sharp distinctions between the theology of the East and the theology of the

West (and for good, historical reasons, at times). All of the world’s problems

are neatly packaged as Western thinking, with Augustine chiefly to blame.

However, I must stress that the extremes of this attitude do not express

normative, dogmatic Orthodoxy.

I’ve

already noted our affinity for St. Augustine, but when it comes to an East and

West divide, the Orthodox Church is not only for ‘Eastern’ or oriental people,

but is believed to be both a catholic and universal faith—encompassing

perspectives both Greek and Latin, Jewish and Gentile. ‘Eastern’ is more of a

description for the sake of clarity than it is anything deeply meaningful or

theological—and far less is it to be taken as the inverse of an insult. If the

Orthodox Church is termed ‘Eastern,’ this is almost always said today to

distinguish between Rome and the remaining Patriarchates and autocephalous

churches that are not in communion with the Pope of the city of Rome. So while

there’s definitely some who would use these terms as a further cause of

distinction or even division, we must remember that it is more a term of

clarification than discrimination.

Jordan

also feels that Orthodox Christians (such as Lossky) are led to false

dichotomies when it comes to doctrinal discussion, as a result of this

anti-Western bigotry. Eastern theology is delivered as the absolute antithesis

to Western theology, with Eastern ideas completely overriding and eliminating

Western ones. For example, Jordan believes that Orthodox Christians accept

one—and only one—viewpoint when it comes to a number of doctrinal distinctives

(such as the atonement), to the exclusion of other, equally valid positions.

Again, I

think this misunderstanding stems from three different factors: 1) An

unfamiliarity with the life and liturgy of the Orthodox Church as one of her

members, 2) An exposure to only certain types of Orthodox literature or

perspectives, and 3) An assumption that particular perspectives among Orthodox

authors—popular as they are—is both a normative and dogmatic expression of the

‘official teachings’ of the Orthodox Church.

And while

this is not entirely Jordan’s fault (even as I term it a ‘misunderstanding’),

from someone living as part of the Orthodox Church for several years now, I

can’t think of anything said about Orthodoxy that is more obviously false. In

truth, Orthodoxy is often called a church of both paradox and mystery. Our

light-hearted response to deeper questions from our non-Orthodox friends is

“It’s a mystery.” Whenever someone begins to ask me, “What’s the official

Orthodox position on—”, I always stop them and say “We don’t have one.”

(Half-joking, of course.)

So while

many Orthodox authors today will speak of Christus victor, ancestral sin,

theosis, and non-juridicial concepts of salvation, this is not the final,

Orthodox word on these issues. Within our ecumenical boundaries of dogma,

anything is open for discussion, dialogue, and healthy debate. While one might

find a dominant perspective in Orthodoxy on certain topics, this does not mean

we reject all other perspectives on the same. An affinity for theosis is not a

rejection of the forgiveness of sins in Christ’s death on the Cross, nor is it

a rejection of concepts like justification or even ‘legal’ metaphors for

salvation.

One must

also keep in mind that the theological discussions and debates of the Orthodox

Church are not necessarily going to neatly ‘line up’ with that of the West

(using the term as a descriptor, not an insult). In fairness, Protestant

theology is largely a reaction against Rome, with much of modern Roman theology

a counter-reaction against Protestantism (and with a great deal of synthesis,

in some cases). With Orthodoxy on the outside-looking-in, we do not always have

a common ground. This contextualization and historical reality should not be

mistaken as a lack of concern on the part of Orthodox Christians for ideas and

concepts that are more central to Protestant or Roman Catholic belief.

To

contend that Orthodox Christians misunderstand Sola fide or that we care more

about theosis than justification is to beg the question that the Orthodox

Church be Lutheran or Reformed in order to be correct. This is, at best, an

abstraction—conflating epistemology with ontology—and only muddies the waters

of meaningful dialogue.

Concluding Thoughts

While it

might seem at this point that I have a number of substantial disagreements with

Jordan on his introduction to Orthodoxy, I haven’t outlined all of the areas in

which we agree (and where he gets things correct). As I listened, I was

impressed by many of the clarifying statements he made, even seeking to

understand Orthodox Christians on their own terms, and not force everything

into categories or perspectives not necessarily shared between Lutheranism and

Orthodoxy. On more than one occasion while listening to his presentation, I was

about to write down another point for response, but he would then provide the

correct and balancing statements in order to more accurately represent the

Orthodox faith.

If there

is any prevailing weakness to his presentation, it’s that he’s looking at

things from the outside-in, and relying on only a few, select sources in order

to do so. I feel that Orthodox Christians are at fault for much of the

popular-level apologetics and other, inaccurate material one might find either

in print or online, but things are always improving. English-language Orthodox

resources on a large and quality scale are very much still in their infancy.

In the

end, I would encourage those interested in learning more about Orthodoxy to not

necessarily start with any one book, but with a simple visit to a nearby

parish. Grab coffee with the priest or deacon, and pick his brain with your

questions or concerns. More often than not, they will be happy to do so, and

without any pressure or presumption that you’re interested in converting.

Attending some services during the week, when it doesn’t conflict with your own

religious attendance on Sunday, is another helpful option (especially during

Great Lent). It’s one thing to read about Orthodoxy, and another thing

altogether to experience it and be exposed to the incarnate reality of the

Church on a regular basis.

I hope

someone finds this ‘conversation’ helpful, and that it clears up any confusion

Lutherans (or other Protestant Christians) might have regarding the Orthodox

Church and faith. I’d also like to wish Jordan the best in his ministry and

efforts, and ask his forgiveness for any areas where I’ve misunderstood or

misrepresented what he had to say.

Source: https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/onbehalfofall/why-are-lutherans-converting-to-eastern-orthodoxy/

CONVERSATION