God the Father is

the fountainhead of the Holy Trinity. The Scriptures reveal that the one God is

Three Persons–Father, Son and Holy Spirit–eternally sharing the one divine

nature. From the Father the Son is begotten before all ages and all time (Psalm

2:7; 2 Corinthians 11:31). It is also from the Father that the Holy Spirit

eternally proceeds (John 15:26). Through Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Spirit,

we come to know the Father (Matthew 11:27). God the Father created all things

through the Son, in the Holy Spirit (Genesis 1; 2; John 1:3; Job 33:4), and we

are called to worship Him (John 4:23). The Father loves us and sent His Son to

give us everlasting life (John 3:16).

Jesus Christ is the

Second Person of the Trinity, eternally born of the Father. He became a man,

and thus He is at once fully God and fully man. His coming to earth was

foretold in the Old Testament by the Prophets. Because Jesus Christ is at the

heart of Christianity, the Orthodox Church has given more attention to knowing

Him than to anything or anyone else. In reciting the Nicene Creed, Orthodox

Christians regularly affirm the historic faith concerning Jesus as they say, “I

believe…in one Lord Jesus Christ, begotten of the Father before all ages, Light

of Light, Very God of Very God, begotten, not made, of one essence with the

Father, by whom all things were made, who for us men and for our salvation came

down from heaven, and was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary, and

was made man; and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate, and suffered

and was buried; and the third day He rose again from the dead, according to the

Scriptures; and ascended into heaven, and sits at the right hand of the Father;

and He shall come again with glory to judge the living and the dead, whose

Kingdom shall have no end.”

The Holy Spirit is

one of the Persons of the Trinity and is one in essence with the Father.

Orthodox Christians repeatedly confess, “And I believe in the Holy Spirit, the

Lord and Giver of life, who proceeds from the Father, who together with the

Father and the Son is worshipped and glorified. . .” He is called the “Promise

of the Father” (Acts 1:4), given by Christ as a gift to the Church, to empower

the Church for service to God (Acts 1:8), to place God’s love in our hearts (Romans

5:5), and to impart spiritual gifts (1 Corinthians 12:7-13) and virtues

(Galatians 5:22, 23) for Christian life and witness. Orthodox Christians

believe the biblical promise that the Holy Spirit is given in chrismation

(anointing) at baptism (Acts 2:38). We are to grow in our experience of the

Holy Spirit for the rest of our lives.

Incarnation refers

to Jesus Christ coming “in the flesh.” The eternal Son of God the Father

assumed to Himself a complete human nature from the Virgin Mary. He was (and is)

one divine Person, fully possessing from God the Father the entirety of the

divine nature, and in His coming in the flesh fully possessing a human nature

from Mary. By His Incarnation, the Son forever possesses two natures in His one

Person. The Son of God, limitless in His divine nature, voluntarily and

willingly accepted limitation in His humanity, in which He experienced hunger,

thirst, fatigue–and ultimately, death. The Incarnation is indispensable to

Christianity–there is no Christianity without it. The Scriptures record, “Every

spirit that does not confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is not of

God” (1 John 4:3). By His Incarnation, the Son of God redeemed human nature, a

redemption made accessible to all who are joined to Him in His glorified

humanity.

Sin literally means

“to miss the mark.” As Saint Paul writes, “All have sinned and fall short of

the glory of God” (Romans 3:23). We sin when we pervert what God has given us

as good, falling short of His purposes for us. Our sins separate us from God

(Isaiah 59:1,2), leaving us spiritually dead (Ephesians 2:1). To save us, the

Son of God assumed our humanity, and being without sin, “He condemned sin in

the flesh” (Romans 8:3). In His mercy, God forgives our sins when we confess

them and turn from them, giving us strength to overcome sin in our lives. “If

we confess our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to

cleanse us from all unrighteousness” (1 John 1:9).

Salvation is the

divine gift through which men and women are delivered from sin and death,

united to Christ, and brought into His eternal Kingdom. Those who heard Peter’s

sermon on the Day of Pentecost asked what they must do to be saved. He

answered, “Repent, and let every one of you be baptized in the name of Jesus

Christ for the remission of sins; and you shall receive the gift of the Holy

Spirit” (Acts 2:38). Salvation begins with these three “steps”: 1) repent, 2)

be baptized, and 3) receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. To repent means to

change our mind about how we have been, turning from our sin and committing

ourselves to Christ. To be baptized means to be born again by being joined into

union with Christ. And to receive the gift of the Holy Spirit means to receive

the Spirit who empowers us to enter a new life in Christ, be nurtured in the

Church, and be conformed to God’s image.

Baptism is the way

in which a person is actually united to Christ. The experience of salvation is

initiated in the waters of baptism. The Apostle Paul teaches in Romans 6:1-6

that in baptism we experience Christ’s death and Resurrection. In it our sins

are truly forgiven and we are energized by our union with Christ to live a holy

life.

Nowadays, some

consider baptism to be only an “outward sign” of belief in Christ. This

innovation has no historical or biblical precedent. Others reduce it to a mere

perfunctory obedience to Christ’s command (cf. Matthew 28:19, 20). Still

others, ignoring the Bible completely, reject baptism as a vital factor in

salvation. Orthodoxy maintains that these contemporary innovations rob sincere

people of the important assurance that baptism provides-namely that they have

been united to Christ and are part of His Church.

New birth is

receiving new life and is the way we gain entrance into God’s Kingdom and His

Church. Jesus said, “Unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot

enter the kingdom of God” (John 3:5). From the beginning, the Church has taught

that the “water” is the baptismal water and the “Spirit” is the Holy Spirit.

The New Birth occurs in baptism, where we die with Christ, are buried with Him,

and are raised with Him in the newness of His Resurrection, being joined into

union with Him in His glorified humanity (Romans 6:3,4). The historically late

idea that being “born again” is a religious experience disassociated from

baptism has no biblical basis whatsoever.

Justification is a

word used in the Scriptures to mean that in Christ we are forgiven and actually

made righteous in our living. Justification is not a once-for-all,

instantaneous pronouncement guaranteeing eternal salvation, no matter how

wickedly a person may live from that point on. Neither is it merely a legal

declaration that an unrighteous person is righteous. Rather, justification is a

living, dynamic, day-to-day reality for the one who follows Christ. The

Christian actively pursues a righteous life in the grace and power of God

granted to all who are believing Him.

Sanctification is

being set apart for God. It involves us in the process of being cleansed and

made holy by Christ in the Holy Spirit. We are called to be saints and to grow

into the likeness of God. Having been given the gift of the Holy Spirit, we

actively participate in sanctification. We cooperate with God, we work together

with Him, that we may know Him, becoming by grace what He is by nature.

The Bible is the

divinely inspired Word of God (2 Timothy 3:16), and is a crucial part of God’s

self-revelation to the human race. The Old Testament tells the history of that

revelation from Creation through the Age of the Prophets. The New Testament

records the birth and life of Jesus as well as the writings of His Apostles. It

also includes some of the history of the early Church and especially sets forth

the Church’s apostolic doctrine. Though these writings were read in the

churches from the time they first appeared, the earliest listing of all the New

Testament books exactly as we know them today is found in the Thirty-third

Canon of a local council held at Carthage in A.D. 318 and in a fragment of

Saint Athanasius of Alexandria’s Festal Letter for the year 367. Both sources

list all of the books of the New Testament without exception. A local council,

probably held at Rome under Saint Damasus in 382, set forth a complete list of

the canonical books of both the Old and New Testaments. The Scriptures are at

the very heart of Orthodox worship and devotion.

Worship is the act

of ascribing praise, glory and thanksgiving to God: the Father, the Son and the

Holy Spirit. All humanity is called to worship God. Worship is more than being

in the “great out-of-doors” or listening to a sermon or singing a hymn. God can

be known in His creation, but that doesn’t constitute worship. And as helpful

as sermons may be, they can never offer a proper substitute for worship. Most

prominent in Orthodox worship is the corporate praise, thanksgiving and glory

given to God by the Church. This worship consummates in intimate communion with

God at His Holy Table.

Worship is the act

of ascribing praise, glory and thanksgiving to God: the Father, the Son and the

Holy Spirit. All humanity is called to worship God. Worship is more than being

in the “great out-of-doors” or listening to a sermon or singing a hymn. God can

be known in His creation, but that doesn’t constitute worship. And as helpful

as sermons may be, they can never offer a proper substitute for worship. Most

prominent in Orthodox worship is the corporate praise, thanksgiving and glory

given to God by the Church. This worship consummates in intimate communion with

God at His Holy Table.

As is said in the

Liturgy, “To You is due all glory, honor and worship, to the Father, and to the

Son, and to the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of ages. Amen.” In that

worship we touch and experience His eternal Kingdom, the age to come, and join

in adoration with the heavenly hosts. We experience the glory of the

fulfillment of all things in Christ as truly all in all.

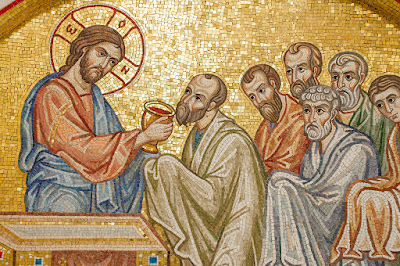

Eucharist means

“thanksgiving” and early became a synonym for Holy Communion. The Eucharist is

the center of worship in the Orthodox Church. Because Jesus said of the bread

and wine at the Last Supper, “This is my body,” “This… is… my blood,” and “Do

this in remembrance of Me” (Luke 22:19, 20), His followers believe-and

do–nothing less. In the Eucharist, we partake mystically of Christ’s Body and

Blood, which impart His life and strength to us. The celebration of the

Eucharist was a regular part of the Church’s life from its beginning. Early

Christians began calling the Eucharist “the medicine of immortality” because

they recognized the great grace of God that was received in it.

Liturgy is a term

used to describe the shape or form of the Church’s corporate worship of God.

The word “liturgy” derives from a Greek word which means “the common work.” All

the biblical references to worship in heaven involve liturgy.

In the Old

Testament, God ordered a liturgy, or specific pattern of worship. We find it

described in detail in the Books of Exodus and Leviticus. In the New Testament

we find the Church carrying over the worship of Old Testament Israel as expressed

in both the synagogue and the temple, adjusting them in keeping with their

fulfillment in Christ. The Orthodox Liturgy, which developed over many

centuries, still maintains that ancient shape of worship. The main elements in

the Liturgy include hymns, the reading and proclamation of the Gospel, prayers,

and the Eucharist itself. For Orthodox Christians, the expressions “the

Liturgy” or “the Divine Liturgy” refer to the eucharistic rite instituted by

Christ Himself at the Last Supper.

Communion of Saints.

When Christians depart this life, they remain a vital part of the Church, the

Body of Christ. They are alive in the Lord and “registered in heaven” (Hebrews

12:23). They worship God (Revelation 4:10) and inhabit His heavenly dwelling

places (John 14:2). In the Eucharist we come “to the city of the living God”

and join in communion with the saints in our worship of God (Hebrews 12:22).

They are that great “cloud of witnesses” which surrounds us, and we seek to

imitate them in running “the race that is set before us” (Hebrews 12:1).

Rejecting or ignoring the communion of saints is a denial that those who have

died in Christ are still part of His Holy Church.

Confession is the

open admission of known sins before God and man. It means literally “to agree

with” God concerning our sins. Saint James admonishes us to confess our sins to

God before one another (James 5:16). We are also exhorted to confess our sins

directly to God (1 John 1:9). The Orthodox Church has always followed the New

Testament practices of confession before a priest, as well as private

confession to the Lord. Confession is one of the most significant means of

repenting and of receiving assurance that even our worst sins are truly

forgiven. It is also one of our most powerful aids for forsaking and overcoming

those sins.

Discipline may become necessary to maintain purity and holiness in the Church and to encourage repentance in those who have not responded to the admonition of brothers and sisters in Christ, and of the Church, to forsake their sins. Church discipline often centers around exclusion from receiving Communion (ex-communication). The New Testament records how Saint Paul ordered the discipline of ex-communication for an unrepentant man involved in sexual relations with his father’s wife (1 Corinthians 5:1-5). The Apostle John warned that we are not to receive into our homes those who willfully reject the truth of Christ (2 John 9, 10). Throughout her history, the Orthodox Church has exercised discipline with compassion when it is needed, always to help bring a needed change of heart and to aid God’s people to live pure and holy lives, never as a punishment.

Mary is called Theotokos, meaning “God-bearer” or “the Mother of God,” because she bore the Son of God in her womb and from her He took His humanity. Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist, recognized this reality when she called Mary, “the mother of my Lord” (Luke 1:43). Mary said of herself, “All generations will call me blessed” (Luke 1:48). So we, in our generation, call her blessed. Mary lived a chaste and holy life, and we honor her highly as the model of holiness, the first of the redeemed, the Mother of the new humanity in her Son. It is bewildering to Orthodox Christians that many professing Christians who claim to believe the Bible never call Mary blessed nor honor her who bore and raised God the Son in His human flesh.

Prayer to the Saints is encouraged by the Orthodox Church. Why? Because physical death is not

a defeat for a Christian. It is a glorious passage into heaven. The Christians

does not cease to be a part of the Church at death. God forbid! Nor is he set

aside, idle until the Day of Judgment.

Prayer to the Saints is encouraged by the Orthodox Church. Why? Because physical death is not

a defeat for a Christian. It is a glorious passage into heaven. The Christians

does not cease to be a part of the Church at death. God forbid! Nor is he set

aside, idle until the Day of Judgment.

The True Church is

composed of all who are in Christ–in heaven and on earth. It is not limited in

membership to those presently alive. Those in heaven with Christ are alive, in

communion with God, worshiping God, doing their part in the Body of Christ.

They actively pray to God for all those in the Church–and perhaps, indeed, for

the whole world. So we pray to the saints who have departed this life, seeking

their prayers, even as we ask Christian friends on earth to pray for us.

Apostolic succession has been a watershed issue since the second century, not as a mere dogma, but

as crucial to the preservation of the Faith. Certain false teachers came on the

scene at that time insisting they were authoritative representatives of the

Christian Church. Claiming authority from God by appealing to special

revelations, some were even inventing lineages of teachers supposedly going

back to Christ or the Apostles. In response, the early Church insisted there

was an authoritative apostolic deposit passed down from generation to

generation. They detailed that actual lineage, showing how its clergy were

ordained by those chosen by the successors of the Apostles chosen by Christ

Himself.

Apostolic

succession is an indispensable factor in preserving unity in the Church. Those

in that succession are accountable to it, and are responsible to ensure that

all teaching and practice in the Church is in keeping with her apostolic

foundations. Mere personal conviction that one’s teaching is correct can never

be considered adequate proof of accuracy. Today, critics of apostolic

succession are those who stand outside that historic succession and seek an

identity with the early Church only. The burgeoning number of denominations in

the world can be accounted for in large measure because of a rejection of

apostolic succession.

Councils of the Church. A monumental conflict (recorded in Acts 15) arose in the early Church

over legalism, the keeping of Jewish laws by the Christians, as means of

salvation “Now the apostles and elders came together [in council] to consider

this matter” (Acts 15:6). This council, held in Jerusalem, set the pattern for

the subsequent calling of councils to settle problems. There have been hundreds

of such councils–local and regional-over the centuries of the history of the

Church, and seven councils specifically designated “Ecumenical,” that is,

considered to apply to the whole Church. The Orthodox Church looks particularly

to these Ecumenical Councils for authoritative teaching in regard to the faith

and practice of the Church, aware that God has spoken through them.

The most important

creed in Christendom is the Nicene Creed, the product of two Ecumenical

Councils in the fourth century. Fashioned in the midst of a life-and-death

controversy, it contains the essence of New Testament teaching about the Holy

Trinity, guarding that life-giving truth against those who would change the

very nature of God and reduce Jesus Christ to a created being rather than God

in the flesh. The creeds give us a sure interpretation of the Scriptures

against those who would distort them to support their own religious schemes.

Called the “Symbol of Faith” and confessed in many of the services of the

Church, the Nicene Creed constantly reminds the Orthodox Christian of what one

personally believes, keeping one’s faith on track.

Icons are images of

Christ, of His angels, of His saints, and of events such as the Birth of

Christ, His Transfiguration, His death on the Cross, and His Resurrection.

Icons actually participate in and thus reveal the reality they express. In the

image we see and experience the Prototype. An icon of Christ, for example,

reveals something of Christ Himself to us. Icons are windows to heaven, not

only revealing the glory of God, but becoming to the worshiper a passage into

the Kingdom of God. The history of the use of icons goes back to the early

Church-Tradition tells us Luke the Evangelist was the first iconographer.

Orthodox Christians do not worship icons, but they honor them greatly because of

their participation in heaven’s reality.

Spiritual gifts.

When the young Church was getting underway, God poured out His Holy Spirit upon

the Apostles and their followers, giving them spiritual gifts to build up the

Church and serve each other. Among the specific gifts of the Spirit mentioned

in the New Testament are: apostleship, prophecy, evangelism, pastoring,

teaching, healing, helps, administrations, knowledge, wisdom, tongues,

interpretation of tongues. These and other spiritual gifts are recognized in

the Orthodox Church. The need for them varies with the times. The gifts of the

Spirit are most in evidence in the liturgical and sacramental life of the

Church.

Second coming. With

the current speculation in some corners of Christendom surrounding the Second

Coming of Christ and how it may come to pass, it is comforting to know the

beliefs of the Orthodox Church are basic. Orthodox Christians confess with

conviction that Jesus Christ “will come again to judge the living and the

dead,” and that “His Kingdom will have no end.” Orthodox preaching does not

attempt to predict God’s prophetic schedule, but to encourage Christian people

to have their lives in order that they might have confidence before Him when He

comes (1 John 2:28).

Heaven is the place

of God’s throne beyond time and space. It is the abode of God’s angels, as well

as of the saints who have passed from this life. We pray, “Our Father, who are

in heaven. . .” Though Christians live in this world, they belong to the

Kingdom of heaven, and that Kingdom is their true home. But heaven is not only

for the future. Neither is it some distant place billions of light years away

in a nebulous “great beyond.” For the Orthodox, heaven is part of Christian

life and worship. The very architecture of an Orthodox church building is

designed so that the building itself participates in the reality of heaven.

Saint Paul teaches we are raised up with Christ in heavenly places (Ephesians

2:6), “fellow citizens with the saint and members of the household of God” (Ephesians

2:19). At the end of the age, a new heaven and a new earth will be revealed

(Revelation 21:1).

Hell, unpopular as

it is among modern people, is real. The Orthodox Church understands hell as a

place of eternal torment for those who willfully reject the grace of God. Our

Lord once said, “If your hand causes you to sin, cut it off. It is better for

you to enter into life maimed, rather than having two hands, to go to hell,

into the fire that shall never be quenched–where ‘Their worm does not die, and

the fire is not quenched’ ” (Mark 9:43, 44). He challenged the religious

hypocrites with the question: “How can you escape the condemnation of hell?”

(Matthew 23:33). His answer is, “God did not send His Son into the world to

condemn the world, but that the world through Him might be saved” (John 3:17).

There is a Day of Judgment coming, and there is a place of punishment for those

who have hardened their hearts against God. It does make a difference how we

live this life. Those who of their own free will reject the grace and mercy of

God must forever bear the consequences of that choice.

Creation. Orthodox

Christians confess God as Creator of heaven and earth (Genesis 1:1, the Nicene

Creed). Creation did not just happen into existence. God made it all. “TB faith

we understand that the worlds were framed by the word of God. . .” (Hebrews

11:3). Orthodox Christians do not believe the Bible to be a scientific textbook

on creation, as some mistakenly maintain, but rather God’s revelation of

Himself and His salvation. Also, helpful as they may be, we do not view

scientific textbooks as God’s revelation. They may contain both known facts and

speculative theory. They are not infallible. Orthodox Christians refuse to

build an unnecessary and artificial wall between science and the Christian

Faith. Rather, they understand honest scientific investigation as a potential

encouragement to faith, for all truth is from God.

Marriage in the

Orthodox Church is forever. It is not reduced to an exchange of vows or the

establishment of a legal contract between the bride and groom. On the contrary,

it is God joining a man and a woman into “one flesh” in a sense similar to the

Church being joined to Christ (Ephesians 5:31, 32). The success of marriage

cannot depend on mutual human promises, but on the promises and blessing of

God. In the Orthodox marriage ceremony, the bride and groom offer their lives

to Christ and to each other–literally as crowned martyrs.

Source: http://www.antiochian.org/whatorthodoxbelieve

CONVERSATION