Time in Icon

To be

able to understand icons it is necessary to know how people of the Middle Ages

perceived and understood the concept of time. The difference between the

concept of time in Western Europe and that in Byzantium was formed in the

Renaissance period, when Europe, unlike Byzantium, acquired the new attitudes

and outlook towards the world.

To be

able to understand icons it is necessary to know how people of the Middle Ages

perceived and understood the concept of time. The difference between the

concept of time in Western Europe and that in Byzantium was formed in the

Renaissance period, when Europe, unlike Byzantium, acquired the new attitudes

and outlook towards the world. After temporal seizure of Constantinople by the

crusaders in 1204 the estrangement between Byzantium and Europe became even

more profound and implacable.

Different

attitudes towards time caused different attitudes towards the world; to the

events in it, and to the role of men in these events. As a result, the meaning

and objectives of art in Byzantium and Western Europe altered too. Because of

these fundamentally different artistic techniques were developed by the artists

of Western Europe and the icon-painters of the Orthodox countries.

Different

attitudes towards time caused different attitudes towards the world; to the

events in it, and to the role of men in these events. As a result, the meaning

and objectives of art in Byzantium and Western Europe altered too. Because of

these fundamentally different artistic techniques were developed by the artists

of Western Europe and the icon-painters of the Orthodox countries.

The

Renaissance revived the notion of history and separated Holy History from lay

history. The prominent Italians – Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374), Leonardo

Bruni (1374-1444) and Lorenzo Valla (1403-1457) began the study of scientific

history.

Lorenzo

Balla, the author of the famous work “Elegances of the Latin Language”, made it

his aim to revive classical Latin, where philosophy, rhetoric and language are

inseparable. Not only did he have to address the heritage of antiquity, but

also to explore the reasons for “language corruption” and culture decline

during “the time of barbarism”. All this led to a retrospective review of

history and historical time.

Time was

now related to change, to cause-and-effect relations of events in their

historical sequence. The conception of historical succession emerged and,

therefore so did the understanding of the depth of time and the awareness of

perspective. Discovery of perspective and historical time coincided, in fact,

with the emergence of the theories on aerial and linear perspective.

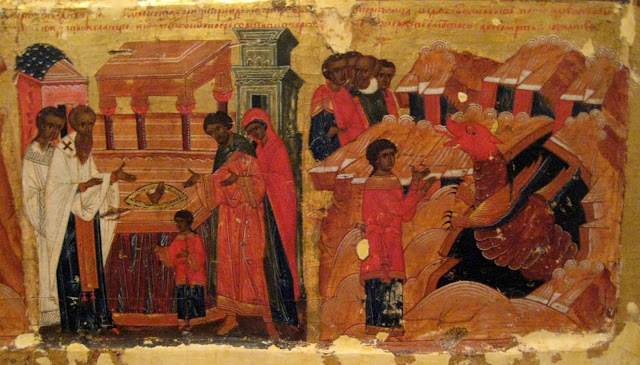

Awareness

of events, taking place in space and time, resulted in the fact that European

artists stopped depicting events that took place at different times

simultaneously in their pictures. For instance, in Giotto’s fresco “Birth of

Mary”, we can see the girl in two places at one time: in the midwife’s arms,

sitting on the floor by the bed, and near her Mother. Such examples are numerous.

New

attitudes to time and new theological thinking, which recognized free will in a

man through which God’s design could find realization, engendered a new man – a

man of conscious action. A man, who created the history of his own life, and

together with other people – the history of their nation (Leonardo Bruni). This

new man could say about himself: “…I make use of my time, being constantly

engaged in some kind of activity, I would prefer to lose my sleep rather than

waste my time.” (Leon Battista Alberti, “On the Family”).

This

approach was prominent in the fine arts. Artists began to study the movements

of the human body, changes in appearance caused by the mood (anger, joy,

laughter, sadness) or ageing processes. Fundamental discoveries were made in

this field and the role of muscles and their specialization was found.The

understanding of movement as opposed to equilibrium gave rise to new

composition methods, for instance removing the center of gravity from the body

and showing unfinished gestures in pictures. This technique makes the viewer

perceive a prolonged movement in the painting.

A passive

man of the Gothic period was replaced by a man of free will. Readiness for

action, for movement was revealed through the strained muscles and the expression

of face and eyes. Looking at the picture we are waiting for action and because

of this the picture is alive; the pulse of time is beating in it.

In the

East of Europe, in Byzantium and Ancient Rus, a previous concept of time and

history, dating back to the Fathers of the Church (St Augustine etc.) was

preserved. Life of a man is a period of time, having the beginning and the end

– from the moment of creation of a man by God to the Second Coming of Jesus

Christ. The event that divided history into two parts – the old and the new –

was the birth of Jesus Christ, God’s Incarnation.

Before

the Creation of the World there was no time either. The concept of time can not

be related to God. It is impossible to say that God “was” or “is” or “will be”.

In Russian it is translated as “existing”, the One who “always was”, “always

is” and “will always be” which is derived from the Hebrew name of God – Jahweh

– existing (He Brings Into Existence Whatever Exists).

God

created the world and time “began”. It began and will end with the Second

Coming of Jesus Christ, when “there will be no more time”. Thus, time itself

turns out to be “temporal”, transient. It is like a “short period” on the

background of eternity where God incarnates his design, creating Adam and knowing

from the very beginning the destiny of his descendants.

God

created the world and time “began”. It began and will end with the Second

Coming of Jesus Christ, when “there will be no more time”. Thus, time itself

turns out to be “temporal”, transient. It is like a “short period” on the

background of eternity where God incarnates his design, creating Adam and knowing

from the very beginning the destiny of his descendants.

God’s

design already exists in complete fullness, which includes everything. Time,

history, life, all the objects, all the people, all the events, and everything

has been given its place. Thus, the cause for any event is not defined in our

earthly world but already exists in a different world. God is the source of

everything that was and will be.

The

earthly life of a man is an interval between the Creation of the World and the

Second Coming. It is a trial before eternity, when time stops. Eternal life is

in store for those who pass this trial.

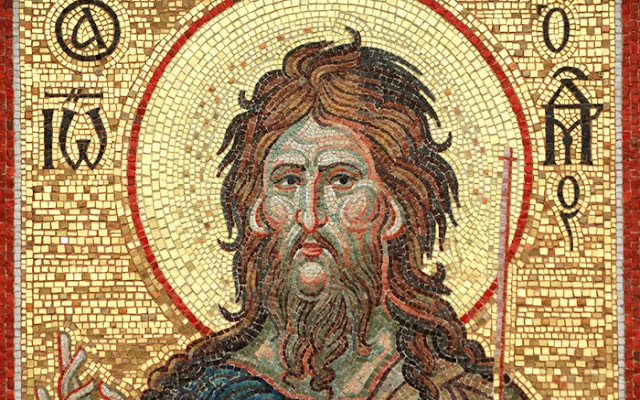

The

saints depicted in the old icons have already been found worthy of eternal

life. They are devoid of movement and change in the ordinary sense. The blessing

fingers of the right hand are not a message from this world. Slender fingers

are lifted without effort. They do not have weight, for there is no heaviness

in the other world. The gaze of a saint is the look from eternity. It is not

blurred by passions – that is why we can only return it in the moments of

spiritual enlightenment. That is why the eyes looking at us from the icons

disturb us and make us feel apprehension, fear, and hope.

What the

old Russian icons depict, does not imply either spatial nor time localization.

The image exists beyond space and time.

Here is

the image “The Saviour” by Andrew Rublov (1360/70-about 1430). The eyes turned

to us from eternity see everything, understand everything and take in

everything and it is precisely for this reason that everything can be found in

the Saviour’s eyes, and everybody always, can apply to Him.

Peculiar

understanding of time and space in Old Russian icon-painting bore fundamental

dogmatic meaning. That is the reason why, in the second half of the 17th

century when Russian icon-painting started to be influenced by western

painting, it evoked so much protest and indignation. Reasons for this were not

the conservatism of icon-painting, but apprehensions of misinterpretation of

the very sense and essence of the icon. It is difficult to deny that mages can

not be painted as though they were alive in icons. The saints are in another

world; in eternity, they do not live earthly lives, characterized by time and

change.

Source: http://www.pravmir.com/time-in-icon/