St. Patrick - an Orthodox Saint?

This may

come as a surprise to many that St. Patrick was and is an Orthodox Saint

centuries before Rome split from the Holy Apostolic Church.

The rule

of thumb for Orthodox Christians is that a Latin Christian who lived after the

Great Schism of 1054, while they may have lived exemplary lives, are not saints

in the full sense of the Church’s understanding. But because he lived from c. 385 to 17 March

460/461 Patrick is considered part of the undivided Church and therefore is an

Orthodox saint.

St. Patrick’s Life

The name

“Patrick” is derived from the Latin “Patricius” which means “highborn.” He was born in the village of Bannavem

Taburniae. Its location is uncertain;

some scholars place it on the west coast of England, while others place it in

Scotland. His father was Calpurnius, a

Roman Decurion (an official responsible for collecting taxes) and a deacon in

the church. His grandfather, Potitus,

was a priest.

This

means that Patrick had a solid Christian upbringing and was well acquainted

with the refinements of Roman civilization.

But he lived on the edge of civilization at a time when the Roman Empire

was under siege by barbarians. When

Patrick was sixteen he was kidnapped by pirates, taken to Ireland, and there

sold as a slave. He was put to work as a

herder of swine on a mountain in County Antrim.

Looking

back on his youth, he recounts:

I was at that time about sixteen years of

age. I did not, indeed, know the true God; and I was taken into captivity in

Ireland with many thousands of people, according to our deserts, for quite

drawn away from God, we did not keep his precepts, nor were we obedient to our

priests who used to remind us of our salvation.

(Confessio §1)

Although

Patrick had a Christian upbringing, he took his faith for granted. This complacency would be shaken by the

calamity of being taken into exile. For

the next six years he spent much of his time in solitude and prayer which would

prepare him for life as a monastic. During this time Patrick also learned the

local language which would prepare him for his future work as a missionary

bishop.

But after I reached Ireland I used to pasture

the flock each day and I used to pray many times a day. More and more did the

love of God, and my fear of him and faith increase, and my spirit was moved so

that in a day [I said] from one up to a hundred prayers, and in the night a like

number. . . . (Confessio §16)

His

escape from slavery resulted from two visions.

In the first vision it was revealed that he would return home. The second vision told him his ship was

ready. He then walked two hundred miles

to the coast, succeeded in boarding a ship, and reunited with his parents.

Sometime

later Patrick studied for the priesthood under St. Germanus in Gaul

(France). Eventually, he was consecrated

as a bishop and entrusted with the mission to Ireland. Patrick had a dream in which he heard the

Irish people begging him to come back to them.

There were other missionaries in Ireland but it was St. Patrick who had

the greatest success. For this reason,

he is known as “The Enlightener of Ireland.”

Evangelizing

the Irish people was not an easy task.

The Irish populace regarded him with hostility and disdain. He was a foreigner and, worst yet, a former

slave. Despite the opposition, Patrick

persevered in his missionary calling and baptized many into Christ. This resulted in churches and monasteries all

across Ireland.

Evangelizing

the Irish people was not an easy task.

The Irish populace regarded him with hostility and disdain. He was a foreigner and, worst yet, a former

slave. Despite the opposition, Patrick

persevered in his missionary calling and baptized many into Christ. This resulted in churches and monasteries all

across Ireland.

In his

autobiography Patrick described his motivation for doing missionary work:

I am greatly God’s debtor, because he granted

me so much grace, that through me many people would be reborn in God, and soon

after confirmed, and that clergy would be ordained everywhere for them, the

masses lately come to belief, whom the Lord drew from the ends of the earth,

just as he once promised through his prophets: ‘To you shall the nations come

from the ends of the earth. . . . (Confessio §38)

St.

Patrick’s missionary labors would result in a blessing, not just to the Irish,

but to humankind as well. How the Irish

Saved Civilization by Thomas Cahill tells how Ireland became an isle of saints

and scholars, preserving Western civilization while the Continent was being

overrun by barbarians.

American

culture has been richly blessed by the presence of the Irish. In the US, March 17th has become something

close to a national holiday. While in

many instances St. Patrick’s day has become more of an excuse for partying, it

can also be made into an occasion for renewing our faith in Christ.

St. Patrick’s Faith

We learn

of his faith through the well known Breastplate of St. Patrick. It is also known as the Lorica (Latin for

‘breastplate.’). In the monastic

tradition a lorica is a prayer/incantation for spiritual protection.

Below are

some excerpts of the rather lengthy but powerful and inspiring prayer. There is a strong masculine and militant tone

in Patrick’s prayer that contrasts with the softer, more feminine quality of

later Christian spirituality.

I arise today

through a mighty strength,

the invocation of the Trinity,

through belief in the Threeness,

through confession of the Oneness of the

Creator of creation.

***

I arise today

through the strength of Christ with His

Baptism,

through the strength of His Crucifixion with

His Burial,

through the strength of His Resurrection with

His Ascension,

through the strength of His descent for the

Judgment of Doom.

Patrick’s

commitment to Orthodoxy can be seen in the third stanza which refers to the

fellowship of the saints and angelic hosts.

His was not the faith of rugged individualism but one marked by a

profound awareness of the interconnectedness with the spirit and biblical

worlds as expressed in the Liturgy.

I arise today

through the strength of the love of Cherubim,

in obedience of Angels, in the service of the

Archangels,

in hope of resurrection to meet with reward,

in prayers of Patriarchs, in predictions of

Prophets,

in preachings of Apostles, in faiths of

Confessors,

in innocence of Holy Virgins, in deeds of

righteous men.

In the

fourth stanza we learn of Patrick’s zeal for holy Orthodoxy and spiritual

warfare against the forces of darkness.

I summon today all these powers between me

(and these evils):

against every cruel and merciless power that

may oppose my body and my soul,

against incantations of false prophets,

against black laws of heathenry,

against false laws of heretics,

against craft of idolatry,

against spells of witches and smiths and

wizards,

against every knowledge that endangers man’s

body and soul.

Christ to protect me today

against poison, against burning,

against drowning, against wounding,

so that there may come abundance of reward.

Living in

dangerous times Patrick was keenly aware of the dangers all around him and

constantly invoked divine protection as he went about his missionary and

pastoral labors.

Honoring St. Patrick Today

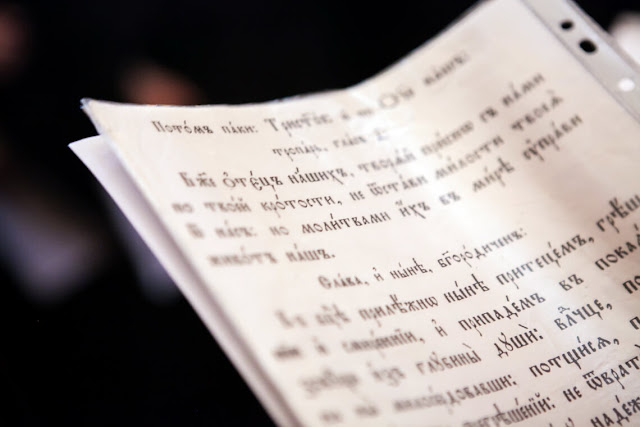

One key

means by which the Orthodox Church honors its saints is by remembering them on

their feast day. Usually during the

Vespers and Matins service preceding the Liturgy, we hear a short summary of

the saint’s life and sing a hymn celebrating God’s work in that saint’s life. The Orthodox Church in America’s website

posted the two hymns for St. Patrick’s feast day:

One key

means by which the Orthodox Church honors its saints is by remembering them on

their feast day. Usually during the

Vespers and Matins service preceding the Liturgy, we hear a short summary of

the saint’s life and sing a hymn celebrating God’s work in that saint’s life. The Orthodox Church in America’s website

posted the two hymns for St. Patrick’s feast day:

Troparion — Tone 3

Holy

Bishop Patrick, / Faithful shepherd of Christ’s royal flock, / You filled

Ireland with the radiance of the Gospel: / The mighty strength of the Trinity!

/ Now that you stand before the Savior, / Pray that He may preserve us in faith

and love!

Kontakion — Tone 4

From

slavery you escaped to freedom in Christ’s service: / He sent you to deliver

Ireland from the devil’s bondage. / You planted the Word of the Gospel in pagan

hearts. / In your journeys and hardships you rivaled the Apostle Paul! / Having

received the reward for your labors in heaven, / Never cease to pray for the

flock you have gathered on earth, / Holy bishop Patrick!

Source: https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/orthodoxbridge/is-st-patrick-an-orthodox-saint/

"A Different Way of Life"

That week, an important event for St. Elisabeth

Convent took place - Metropolitan Pavel of Minsk and Zaslavl tonsured the

sisters of the convent as nuns. The tonsuring was held in the church in honor

of the Reigning icon of the Mother of God at the festal service.

After the Divine service, Metropolitan Pavel

congratulated all with the feast day or the Reigning icon of the Mother of God,

and the newly tonsured nuns – with the beginning of a different life.

March 15, 2017

St. Elisabeth Convent

The Role of Monasticism in the Byzantine and Ottoman States

With the development of Monasticism during the fourth century and thereafter, many monastics became involved with the various heresies, especially those concerning the Christological dogma. Most of the monastics were the defenders of the Orthodox faith. Still, Eutyches, an archimandrite from Constantinople, headed the heresy of monophysitism. On the Orthodox side, St. Maximos the Confessor (c. 580-662) played an important role in defeating the heresies of monothelitism and monoenergism. The Sixth Ecumenical Council (680) condemned monothelitism and reestablished the doctrine of Chalcedon. During the time of the iconoclastic controversy, the Studite monks, led by St. Theodore the Studite (759-826), played a very important role. In addition to organizing his monastery, the Studion, on the basis of the cenobitic principles of St. Pachomios and St. Basil, St. Theodore also wrote his three Antirrhetics against iconoclasm.

After the

condemnation of the iconoclasts, monasticism thrived even more. Many

representatives of the Byzantine aristocracy became monks. Monks were men of

letters; clergy received their education in the monasteries. Bishops,

metropolitans, and patriarchs were taken from their ranks; monks were involved

with the church affairs, at times for the good of the church, at times creating

trouble. Monasteries existed in almost every diocese, with the Bishop as their

head, planting a cross in their foundations. Since 879, the right was given to

the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople of planting a cross in monasteries

that were under the jurisdiction of other dioceses throughout the empire. They

were called "Patriarchal Stavropighiac Monasteries." This right

exists to our days.

With the Arab

conquest of Syria, Palestine and Egypt (during the 7th century), new centers

for monasteries were sought and founded, among which were Mount Olympus in

Bithynia and the Holy Mount Athos.

During the entire

Byzantine period, the monks took an active part in the life of the Church in

general. Still, spirituality was their strength. Concerning this tension in

Christian anthropology, two schools of thought were represented; that of

Evagrios ponticus (d. 399), who followed a Platonic and Origenistic doctrine

pertaining to the "mind," thus de-emphasizing the importance of the

human body and becoming dualistic, and St. Makarios of Egypt (or, better, the

writings attributed to him), present a more Christian, holistic anthropology;

for in this theology man is a psycho-physical entity, and, as such, being a

destined to deification. "Prayer of the mind," in the Evagrian

spirituality, becomes "prayer of the heart" in the Macarian

spirituality. The two schools of thought with the two different anthropologies

continue to find representatives throughout the history of the Church.

Saint Symeon, the

New Theologian (949-1022), marks an important development in monastic

spirituality. A disciple of a Studite monk, he left the Studion to join the

small monastery of St. Mamas in Constantinople, were he was ordained a priest

and became the abbot. He wrote several works, among which are the fifty-eight

hymns of "Divine Love," in which he stresses that the Christian faith

is a conscious experience of God. St. Symeon is the exponent of an intensive

sacramental life, which leads to this personal conscious experience, as we can

see in his Hymns. In this he is a predecessor of Hesychasm, which also shares

this personal experience of God in conjunction with intensive sacramental life.

Finally, the

spirituality of Hesychasm, as enunciated in the theology of St. Gregory Palamas

(1296-1359), is of paramount importance not only in the life of monasticism,

but also in the life of the entire Church. An Anthonite monk, St. Gregory took

it upon himself to defend the holy Hesychasts of the Holy Mountain in their

ways of praying and experiencing the presence of God the "uncreated

light" that they contemplated. Barlaam the Calabrian had led the attack

against the pious monks and their psycho physical method of prayer, and accused

them of "gross materialism," Messalianism, calling them "navel-souls"

(omphalopsychoi) and "navel-watchers" (omphaloskopoi).

The hesychastic

method of prayer consists of regulating one's breathing with the recitation of

the "Jesus prayer": "O Lord, Jesus Christ, Son of God, have

mercy on me, a sinner." The prayer is repeated constantly until it

descends from the lips and minds into one's heart. At the end of the process,

the peace of Christ is poured into the heart of the worshipper, and the light

itself of Christ shines upon him and around him. This light, as that of the

Holy Transfiguration of Christ, may also be seen by our physical eyes.

After the fall of

Constantinople, the number of idiorrythmic monasteries continued to grow, a

fact which brought a further decline to monastic life. The 16th century was the

lowest ebb. In reaction to this problem, many of the monks themselves,

especially on the Holy Mountain, left the main monasteries and turned to

idiorrhythmic ones, establishing Sketai (dependencies) of the main monasteries,

with a more rigorous typikon (order). Also, Patriarchs Jeremy II of

Constantinople, Silvester of Alexandria, and Sophronios of Jerusalem led the

attack against idiorrhythmic monasticism, thus managing to counteract its spread.

Cenobitic monasticism prevailed for a while, but the tide soon went in its

original direction. Many monasteries of the Holy Mountain, including the mother

monastery, the Great Lavra, became idiorrhythmic. Today an idiorrhythmic

monastery may become cenobitic but not the other way round. Hopefully, this

will guarantee that organized monastic life will finally prevail, according to

the Basilian ideal of monasticism.

Monasticism played

an important role under the Ottoman Empire, as well. The monks not only kept

the faith alive, but they also kept the Greek culture and literature alive. Not

only did the education of clergy continue at the monasteries, but the

monasteries became the "clandestine school" (Krypho Scholeio) for all

the Greeks under Turkish occupation. The monks thus prevented the Christian

nations under Turkish occupation from being assimilated to them, and thereby

became the natural leaders of national ("ethnic") resistance against

the oppressors. It is no accident that the Greek Revolution started in 1821 at

a monastery in the Peloponnesos, Aghia Lavra, with Metropolitan Germanos of Old

Patras raising the banner of revolution and blessing the arms of the Greek

freedom fighters.

Illness and Prayer

Our Saviour has taught us: Ask and it shall be given you; seek and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you. For everyone that asketh, receiveth (Matt. 7:7-8).

Therefore, when we are in pain we must

pray for understanding of our malady, patience to bear it, and deliverance from

it, if such be God's holy will. We are also expected to ask for the prayers of

others and especially of the Church, for the effective fervent prayer of a

righteous man availeth much (James 5:16).

"Anyone who is sick should seek

the prayer of others, that they may be restored to health; that through the

intercession of others the enfeebled form of the body and the wavering footsteps

of our deeds may be restored to health....Learn, you who are sick, to gain

health through prayer. Seek the prayer of others, call upon the Church to pray

for you, and God, in His regard for the Church, will give what He might refuse

to you" (St. Ambrose, On the Healing of the Paralytic).

The great public prayer of the Church

for those who are ill is the Service of Holy Unction. This Service, which is

long and exceedingly rich in readings from Scripture, and contains numerous

allusions to biblical figures who were healed by the power of God, gives, in

concentrated form, the Church's teaching about healing.

This Service identifies Christ as the

"Physician and Helper of the suffering," and invokes upon the sick

person, through anointing, the grace of the Holy Spirit, Who heals both souls

and bodies. Since God "mercifully gave us command to perform Holy Unction

upon Thy sick servants," Christ Himself is spoken of as the

"incorruptible chrism" Who in old times had chosen the olive-branch

to show Noah that the Flood had abated. (From ancient times olive oil was used

in the making of Holy Oil.) At the time of the Flood, the olive-branch

symbolized tranquility and safety; so now the priest prays that the Saviour

will, through the "tranquility of Thy mercy's seal [the anointing with

oil]," heal the sufferer.

Acknowledging that illness sometimes

comes through the activity of demonic powers, the priest asks: "Let no

interposition of malignant demons touch the senses of him who is marked with

Thy divine anointing." Showing that the Church also understands the

connection between sin and suffering, the priest prays that through this

anointing the "suffering of him who is tormented by the violence of

passions" may be washed away.

This healing service explores many

aspects of sin, suffering and healing; it is a profound and very exalted

service of prayer and intercession. One very important point should be made

here: during Holy Unction we beg God to remove the sickness — but, in place of

illness, we ask Him to give "the joy of gladness" (anointing itself

is spoken of as the oil of gladness in the Psalms), so that the formerly sick

person might now "glorify Thy divine might." Therefore, one of the

purposes of healing is to enable the sufferer to resume his healthy and active

service to God. In token of this, the Saviour's healing of Peter's

mother-in-law is spoken of: whereupon the fever left her, and she arose and

ministered unto them. This is very important for us to remember: when we are

set free from the torment of bodily sickness, we are expected to fill our

mouths with praise of God and serve Him by amending our sinful ways and living

from henceforth only for God and the world to come, counting this world as

nothing.

Many do not discover prayer until they

are on a sickbed. And those who have all of their lives piously participated in

the public prayer of the Church, discover during illness that they have sadly

neglected the treasures of private or interior prayer. St. Gregory Nazianzen, a

great man of prayer even when his health was good, exclaimed during his last

illness: "The time is swift, the struggle is great, and my sickness

severe, reducing me nearly to immovability. What then is left but to pray to

God?" (Letters).

During illness, prayer is capable of

revealing true and lasting treasures, "for if you have bodily strength,

the inroads of disease stop any joy you may have had from that source...because

anything that belongs to this world is liable to damage and is unable to give

us a lasting pleasure. But piety and the virtues of the soul are just the

opposite because their joy abides forever....If you pour out continued and

fervent prayers, no man can spoil you of their fruit, for this fruit is rooted

in the heavens and protected from all destruction because it is beyond mortal

reach" (St. John Chrysostom, On the Statues).

Two incidents from the lives of the

saints show how simple yet incorruptible this prayer can be. In the life of

Elder Hieroschemamonk Parthenius of the Kiev Caves Lavra we learn that in his

final illness, even after he had been given Holy Unction, he continued to

perform his daily prayer rule of reading the entire Psalter. The day before his

repose he said to his spiritual children:

"Soon, soon I shall leave.

Yesterday I already could not complete my Psalter — only half of it."

"Is it possible, Father, that

until yesterday you said all of your customary rule?"

"Yes, the Lord helped me; after

all, I now do it by memory; I cannot do it with my lips; there is nothing to

breathe with; but yesterday I could not complete it even by memory, for my

memory is leaving me. Only to the Jesus Prayer and to the praises of the Mother

of God do I cling unceasingly" (Orthodox Life, no. 3, 1969).

And in the life of St. Abba Dorotheus

we read about the touching death of his disciple, St. Dosithe-us, who had been

in the monastery only five years, but "died in obedience, at no time and

in nothing having done his own will and having done nothing out of

attachment." He had always practiced the Jesus Prayer, and when his

illness became severe, St. Abba Dorotheus said to him:

"Dositheus, take care over the

Prayer; see that you be not deprived of it."

"Very well, Father," replied

the monk, "only pray for me."

When he had become still worse, St.

Abba Dorotheus said to him:

"Well, Dositheus, how is the

Prayer? Does it continue as before?"

He answered him: "Yes, Father, by

your prayers."

When, however, it became extremely

difficult for him and the illness became so severe that he had to be carried on

a stretcher, Abba Dorodieus asked him:

"How is the Prayer,

Dositheus?"

He answered: "Forgive me, Father,

I cannot keep it up any longer." Then Abba Dorotheus said to him:

"And so leave the Prayer, only

keep God in mind and represent Him to yourself as if He were before you"

(The Orthodox Word, vol. 5, no. 3).

Finally, we see a glorious and

inspiring example of the place of prayer in times of illness in St. Gregory

Nazianzen's account of his own father's illness:

"He suffered from sickness and

bodily pain. The time of my father's sufferings was the season of the holy and

illustrious Pascha, the Queen of Days, the brilliant night which dissipates the

darkness of sin. Of what kind his sufferings were, I will briefly explain: his

whole body was on fire with a great and burning fever; his strength failed him,

he could take no food, his sleep had departed from him, and he was in the

greatest distress. His whole mouth was so ulcerated that it was difficult and

even dangerous to swallow even water. The skill of physicians, the prayers of

his friends, earnest though they were, and every possible attention, were alike

of no avail. In this desperate state his breathing was short and fast and he

had no perception of present things.

"The time of Divine Liturgy was

come, when all due order and silence is kept for the solemn rites. At this moment

my father was raised up by Him Who quickens the dead. At first he moved

slightly, and then more decidedly. Then, in a feeble and indistinct voice, he

called a servant by name to bring his clothes and support him with his hand.

The servant came in alarm and gladly waited upon him while he, leaning upon the

servant as upon a staff, imitated Moses on the mountain and arranged his feeble

hands in prayer...

"He retired again to his bed and,

after taking a little food and sleep, his health slowly recovered so that on

the first Sunday after the Fest of Pascha he was able to enter the church and

offer thanksgiving...

"During this sickness he wan at

no time free of pain. His only relief was Divine Liturgy, to which his pain

yielded, as if to an edict of anishment" (On the Death of His Father).

The acknowledgment of oneself as

deserving temporal and eternal punishment precedes the knowledge of the Saviour

and leads to knowledge of the Saviour.

By Bishop Ignatius Brianchaninov

Communion of the Taboric Light

There are

events seemingly out of season, but holy. Thus, St. Seraphim of Sarov foretold

that Pascha would be celebrated in the summer at the transfer of his relics.

And truly, bringing the saint’s relics to Diveyevo, the thousands of pilgrims

in the crowd could not help giving voice to the Paschal hymns filling their

hearts. Similarly, now, in the midst of March, we must move in thought to

August 19.

And while the crowd was proceeding,

All of a sudden, someone stirred:

It was the sixth of August, meaning,

—the Transfiguration of Our Lord.

We are

compelled by the memory of St. Gregory Palamas, celebrated on the second Sunday

of Lent, to reflect upon the Transfiguration. The life of St. Gregory can

attract interest by its various details and events. For example, he was elected

to the See of Thessaloniki by the direct intercession of the city patron—the

Great Martyr Demetrios. “I take him as archbishop of my city,” St. Demetrios

said to Great Martyr George, and the future archbishop was honored to hear the

conversation of the glorious great martyrs in a nighttime vision. St. Gregory

represented the part of the hierarchy that had more desire for a cell and books

than for glory and vanity. It is only out of obedience and for the good of the

people of God that such people take upon themselves with sorrow the yoke of

administering their flock and the responsibility for many. Archpastorship was a

cross all the heavier in that bishops, just as kings, were often deposed,

banished, and confined in prisons. St. Gregory had to spend a year in captivity

to Turkish pirates, where he preached to them the Gospel and came to the

conclusion that the Greeks must immediately (!) begin to convert the Turks to

Christianity. But all of this and many other sacred facts of his sacred

biography fade into the background when we become acquainted with the main work

of St. Gregory’s life—the dogma of the deification of man and the Taboric

light.

We are

compelled by the memory of St. Gregory Palamas, celebrated on the second Sunday

of Lent, to reflect upon the Transfiguration. The life of St. Gregory can

attract interest by its various details and events. For example, he was elected

to the See of Thessaloniki by the direct intercession of the city patron—the

Great Martyr Demetrios. “I take him as archbishop of my city,” St. Demetrios

said to Great Martyr George, and the future archbishop was honored to hear the

conversation of the glorious great martyrs in a nighttime vision. St. Gregory

represented the part of the hierarchy that had more desire for a cell and books

than for glory and vanity. It is only out of obedience and for the good of the

people of God that such people take upon themselves with sorrow the yoke of

administering their flock and the responsibility for many. Archpastorship was a

cross all the heavier in that bishops, just as kings, were often deposed,

banished, and confined in prisons. St. Gregory had to spend a year in captivity

to Turkish pirates, where he preached to them the Gospel and came to the

conclusion that the Greeks must immediately (!) begin to convert the Turks to

Christianity. But all of this and many other sacred facts of his sacred

biography fade into the background when we become acquainted with the main work

of St. Gregory’s life—the dogma of the deification of man and the Taboric

light.

Nobody

specially prepared this question; it arose as if on its own, gradually

signifying the genuine chasm between the distinct goals of life within

Christianity and the various types of piety. It was precisely the feast of the

Transfiguration that became the point of focus and the shield upon which their

spears broke. What happened on Tabor? What did the Apostles see, and why did they

see what they saw? Gregory’s opponents said that the light seen by the apostles

is a special, enlightening light, but it is created light, like the sunlight

that gives life to all nature.

St.

Gregory, expressing the from thenceforth Orthodox dogma, and clothing in words

the previously accrued but unformalized experience, spoke of the Uncreated

Divine light. The Taboric light is not created, he said, but it is the light

and grace of God Himself, manifested so that those communing of this light

would not die, but be sanctified. Christ was not so much transfigured, says the

Church, as Christ transfigured the vision and senses of the disciples, that

they would be able to see Christ, as He is. This contemplation is a foretaste

of the future Kingdom, of which is said, The glory of God did lighten it [the

Heavenly Jerusalem], and the Lamb is the light thereof (Rev. 21:23). Therefore,

it was said before the Transfiguration that there be some standing here, which

shall not taste of death, till they see the kingdom of God (Lk. 9:27). There is

nothing in all of created nature like the vision of the Kingdom of God that the

apostles saw on Tabor. And therefore Moses, from Sheol, and Elijah, from

Heaven, appeared to Christ, that the Law and Prophets would bow down to the

Word become flesh, and this flesh deified at that.

In

meaning and value, the feast of the Transfiguration is far beyond the bounds of

being just one of the feasts, but gives meaning to all of life and communicates

a purpose. The purpose is theosis. St. Peter says, Whereby are given unto us

exceeding great and precious promises: that by these ye might be partakers of

the Divine nature (2 Pt. 1:4). St. John says, Beloved, now are we the sons of

God, and it doth not yet appear what we shall be: but we know that, when He

shall appear, we shall be like Him; for we shall see Him as He is (1 Jn. 3:2).

St. Peter and St. John were with Him on the holy mountain. St. John’s brother

St. James was there as well, and he would have written about it too had he not

become an early victim of Herod’s wickedness.

Thus, we

will see Him and will be like unto Him, changing because of this very vision

and feeding upon grace, just as the angels feed upon it even now. To bring this

feast to naught, to give it a private, local character instead of its semantic

value, is, it would seem, impossible. However, Western religious thought does

precisely that, not giving due deference to the Transfiguration and to the very

idea of theosis. The Transfiguration is barely noticeable in the Catholic

liturgical year, the teaching of St. Gregory is considered heretical, and the

abyss in worldviews, which we spoke of in the beginning, has become practically

impassable over time. The West tread the path of intellectualism. St. Gregory’s

opponent—Barlaam—said that the vision of God is a mental perception of the

Godhead, but in no way partakes of the eternal light or Uncreated energies. The

East and West took different paths from this point.

The West,

trusting the mind and for reasoning forsaking the main value, philosophized,

speculated, and pondered questions until it lost faith itself and replaced

grace with syllogisms. And we, being in a long Western captivity, absorbed and

embodied all its mistakes. We can criticize the West only as we rid ourselves

of the disease of the West. Otherwise, such criticism will be suicidal. For

centuries our seminarians and academics, priests and bishops neither heard nor

spoke about what St. Gregory taught. That his memory was regularly celebrated

on the second Sunday of Great Lent only emphasizes the bitterness of this.

Hesychasm and the prayer of the heart, not finding a place in academies and

seminaries, nestled into humble monasteries, where they continued to live the

apostolic experience of the Taboric contemplation. This often happened without

books, as the oral transfer of personal experience—that is, as genuine

Tradition. St. Job of Pochaev spent many days in prayer in the stone caves, and

the monks saw the tongues of flame, which did not burn, bursting forth from the

entrance to this natural cell. St. Seraphim, beloved of all, the transfer of

whose relics once brought Pascha in the middle of the summer, also partook of

the Taboric light. He revealed this grace, as the fruit of long prayers and

wise silence in God, to the eyes of Motovilov, and few are those Orthodox

Christians who have not heard about it. St. Sergius would stand at Liturgy as

if in fire, and fire would enter the chalice as he served, and of this fire he

would partake. The best sons of our Church were practical exponents and

fulfillers of Orthodox dogma, although few of them could theoretically

interpret this dogma.

In

conclusion, we can say that the divide between the East and West on the

question of salvation is the difference between intellectualism and human

righteousness on one side, and genuine holiness and a basic change in fallen

nature on the other. But let’s note a few dangerous traps.

First,

not all Orthodox participate in God’s grace in due measure. Confession of true

doctrine is only an indication of the true path. But we must walk this path,

not just point to it. Therefore, we do not need to boast. Second, the Western

path of mental speculation is not that of an absolute impasse. They have

discoveries and useful knowledge there. It is another matter that this path has

an end and boundaries, beyond which it is not within their powers to go, and

there begins the time for other labors and other podvigs. Just to disregard

their knowledge, books, and reflections is a sin. St. Gregory, expressing the

most exalted dogmas of the Church, was a very educated person. Those sciences,

which he did not take as salvific, were respected by him and he was familiar

with them to a due degree. In his youth he studied Aristotle, and at one of his

lectures, read at the court, shouts rang out, “Aristotle himself, were he here,

would not fail to praise it!” That is, it’s not rejecting external knowledge,

but pointing to its limits that is characteristic of Orthodoxy.

First,

not all Orthodox participate in God’s grace in due measure. Confession of true

doctrine is only an indication of the true path. But we must walk this path,

not just point to it. Therefore, we do not need to boast. Second, the Western

path of mental speculation is not that of an absolute impasse. They have

discoveries and useful knowledge there. It is another matter that this path has

an end and boundaries, beyond which it is not within their powers to go, and

there begins the time for other labors and other podvigs. Just to disregard

their knowledge, books, and reflections is a sin. St. Gregory, expressing the

most exalted dogmas of the Church, was a very educated person. Those sciences,

which he did not take as salvific, were respected by him and he was familiar

with them to a due degree. In his youth he studied Aristotle, and at one of his

lectures, read at the court, shouts rang out, “Aristotle himself, were he here,

would not fail to praise it!” That is, it’s not rejecting external knowledge,

but pointing to its limits that is characteristic of Orthodoxy.

Therefore,

being at such a great distance from personal theosis, and in need firstly of

cleansing, correction, and learning, we still know that the final purpose of

human life is the transfiguration of our nature by grace and communion with the

Divine life. On earth it is partial, in seed form, but in eternity it is

different. Thus, to speak about it now is impossible.

An article by Archpriest Andrei Tkachev

Translated

by Jesse Dominick (Pravoslavie.ru)

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)

About Our Blog

Welcome to the official blog of the Catalogue of St.Elisabeth Convent! The blog includes recent ministry updates of the convent, sermons, icons, personal stories and everything related to Orthodox Christianity. Join our Catalog of Good Deeds and become part of the ministry of St.Elisabeth Convent! #CatalogOfGoodDeeds